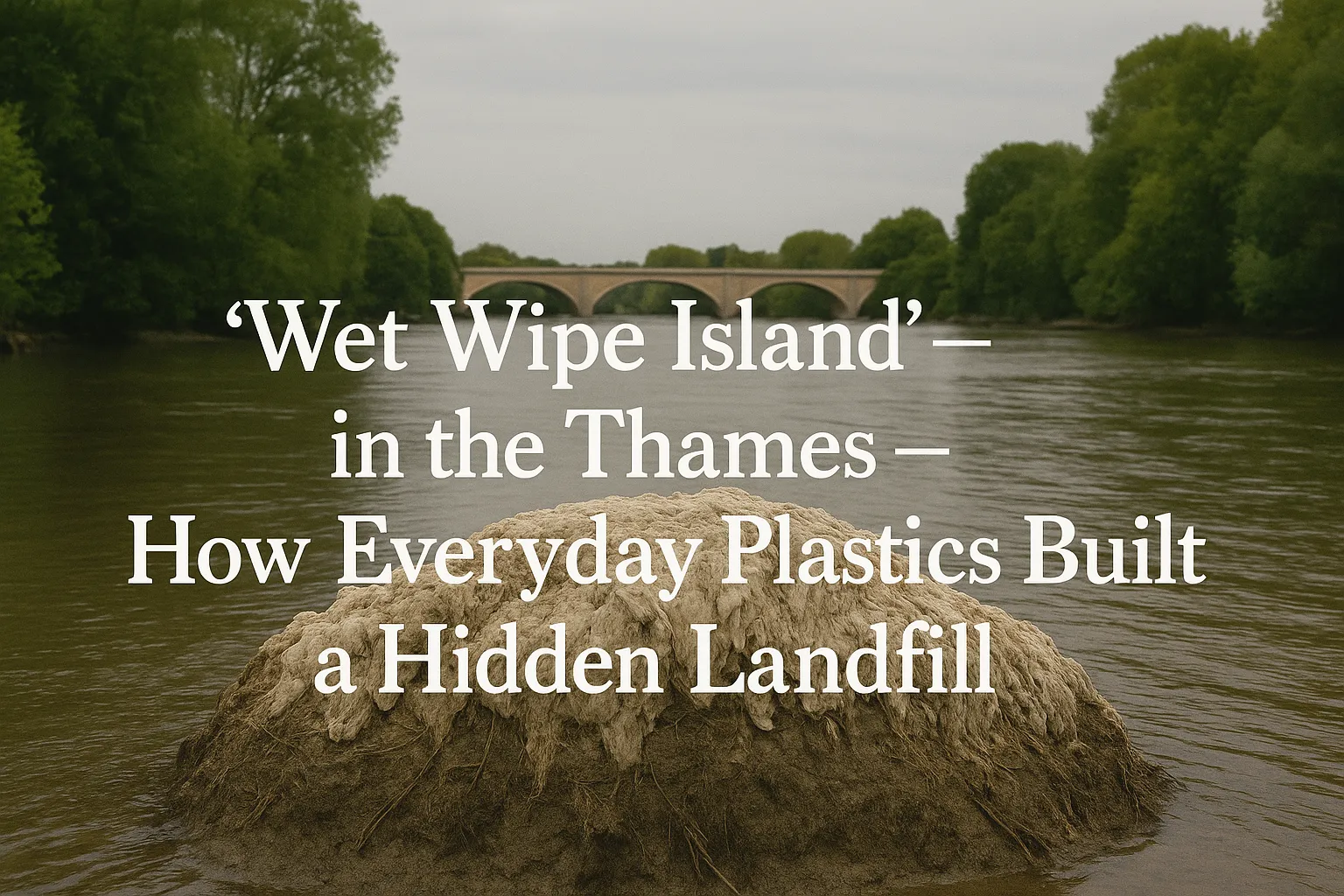

Wet Wipe Island in the Thames How Everyday Plastics Built a Hidden Landfill

Along tidal bends of the Thames, matted clumps of so‑called “flushable” wipes mix with twigs, fat, and silt. Over time they knit together, raising the riverbed and creating banks that look natural at a glance—but are mostly plastic. Here’s how we got here, why it matters, and what turns the tide.

What Exactly Is a “Wet Wipe Island”?

It’s a man‑made mound on the riverbed formed by millions of wipes snagging on roots, pilings, and debris. Tides compact the mesh‑like fibers; more material sticks, and the mound grows. Because most wipes contain polyester or polypropylene, they persist for years and shed microplastics downstream.

How Do So Many Wipes Reach the River?

- Bathroom bin vs. bowl: A portion of households still flush wipes—baby, make‑up, “antibacterial” and even those marketed as flushable.

- Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs): During heavy rain, overflow points discharge diluted wastewater to prevent backups; wipes already in the system escape to rivers.

- Fatbergs: Oils and wipes congeal into blockages; when they break apart, fragments feed new accumulations.

- Greenwashing labels: “Biodegradable” can mean breaking down under specific industrial conditions—not in cold, low‑oxygen rivers.

Why It’s a Big Problem

- Ecology: Microfibres are ingested by invertebrates and fish, moving up the food web.

- Flood risk: Raised beds and snag points push water sideways, worsening bank erosion and local flooding.

- Navigation & amenity: Accreted banks alter flows near bridges and moorings; litter harms recreation and tourism.

- Maintenance costs: Utilities spend millions clearing blockages that wipes help create.

What Labels Really Mean

| Label on Pack | Plain‑English Translation | Best Disposal |

|---|---|---|

| “Flushable” | May pass through a toilet; likely persists in pipes and rivers. | Bin it. |

| “Biodegradable” | Breaks down eventually under specific conditions (often not rivers). | Bin or food‑waste only if certified and unused with chemicals. |

| “Plastic‑free” | Made from cellulose/viscose; still forms rags in sewers. | Bin it. |

What Actually Works (Layered Fixes)

- Policy: Ban plastic in wipes or require conspicuous “Do Not Flush” front‑of‑pack warnings; standardize tests that reflect real sewer conditions.

- Infrastructure: Expand storage tanks and screening at CSOs; deploy finer nets where feasible; accelerate sewer relining to cut snag points.

- Retail & product: Shift shelves toward plastic‑free, truly compostable cleaning options; promote reusable cloths and refillable sprays.

- Behavior: Bin, don’t flush. Keep a lidded bathroom bin; never pour fats/oils down the sink.

- Clean‑ups: Tidal‑timed volunteer events can remove tonnes in hours when coordinated with river authorities.

Starter Kit for a Community River Clean‑Up

- Pick a low‑tide window; confirm permissions with the local river authority.

- Provide gloves, litter pickers, woven sacks, sharps boxes, and clear safety briefings.

- Separate wet wipes from organic debris where possible; log weights to track progress.

- Dispose via municipal waste and share results with local media to build momentum.

“Wet Wipe Island” isn’t inevitable. With honest labels, better sewers, and a simple bathroom habit change, the Thames can stop accumulating plastic banks and start breathing like a river again.